I had in mind (and in my grant writing) to focus on making instead of teaching, connecting with artists working in different media from across the globe and to learn more about harakeke and Maori culture during my artist residency at CollaboratioNZ. I had first been introduced to harakeke in 2012 when I was invited to teach several felting workshops in New Zealand. I was gifted flowers by a number of participants made from split and woven leaves of this NZ flax plant that I still have in my house today. I quickly learned that it wasn’t the same flax plant, Linum usitatissimum, the stalks of which are processed into linen, but rather the leaves of the native Phormium tenax, or harakeke in the Maori language, that is processed. Just like varieties of wool, there are numerous cultivars of harakeke with different characteristics that are preferred for specific uses.

Wendy Naeplfin, a current CollabNZ committee member and flax weaver seen here with a delivery of fresh harakeke leaves, gathered me into the passenger seat of her car (leftside!) from the bus stop in the town basin of Whanagerai and we wound our way out to the headlands. Upon arriving at the camp I met two more flax weavers, Raewyn Rouse and Elke Radewald. As I brought my studio items up to the fiber tent, I realized that these three would occupy the first two tables at the entry of the tent and occupied they definitely were! There was always a steady flow of artists seeking to collab with a harakeke weaver, a sheer sign of this plants cultural relevance and appeal to not only those of Maori heritage, but a broad swath of New Zealanders.

In my first INTRIGUE/BLOG post about CollabNZ, I described the making of the piece “Structural Change” sequentially from start to finish, simply because it was the first piece I started and certainly the most time involved. However, within a couple days I had 8 different pieces I was committed to working on and every one of them incorporated harakeke!

Elke is pictured here weaving strips of the harakeke leaf into a 2D plane while a line up of glass pieces await a fiber flourish or, in the case of that green bulbous vessel, to be nearly encased with a woven skin of harakeke leaves. I was fortunate to have my work station immediately next door and as I watched Elke develop hollow forms, I began to chat with her about the possibility of combining these seemingly disparate materials; hers being a coarser version of cellulostic bast fiber that needs to be processed into smaller elements to build forms and mine, thousands of individual wool filaments that need to be matted into a singular mass to sculpt hollow form. Felting would also be considered by many to be a more coarse version of wool textile compared to spinning and then weaving, knitting, crocheting, etc.

As mentioned above in regards to the naming of NZ flax, harakeke leaf is processed into fine strong fiber. Below, Raewyn uses a shell, a traditional method, to cut into and scrape away the flesh of the outer leaf, revealing the inner fiber, commonly referred to by the Maori word, muka. The quantity of processed muka on the table in front of Raewyn and I represents so much work in and of itself! In the same photo on the left side, you can see on how the fibers are aligned at the top where Wendy has started to use a finger weft-twining technique (whatu) to bind the vertical warp fibers (whenu), which is the foundation of the amazing tradition of Maori cloak weaving. Honest, there were so many projects happening at this station, I can’t recall what Wendy was working toward with this piece!

Back in 2012, after I had finished my teaching obligations, I had rented a car to do a bit of exploring and visited the Whakarewarewa Thermal Village in Rotaroa. There, I saw my first piupiu, a skirt created by this process of removing sections of the outer flesh of the leaf in a strategic pattern that not only created a color contrast of leaf and fiber that could be accentuated by dyeing, but also a variation of texture and flexibility. As the sections of leaf dried they curled into a cylinder producing a distinct sound when they would rattle against one another as a result of the sway and flex of the muka fibers and the person wearing it. I was fascinated and given a length of this leaf and muka cording as a result of my diligent inquiry, but I hadn’t seen the process actually done until Raewyn began processing the leaves for a collaborative vision that all three weavers were working on.

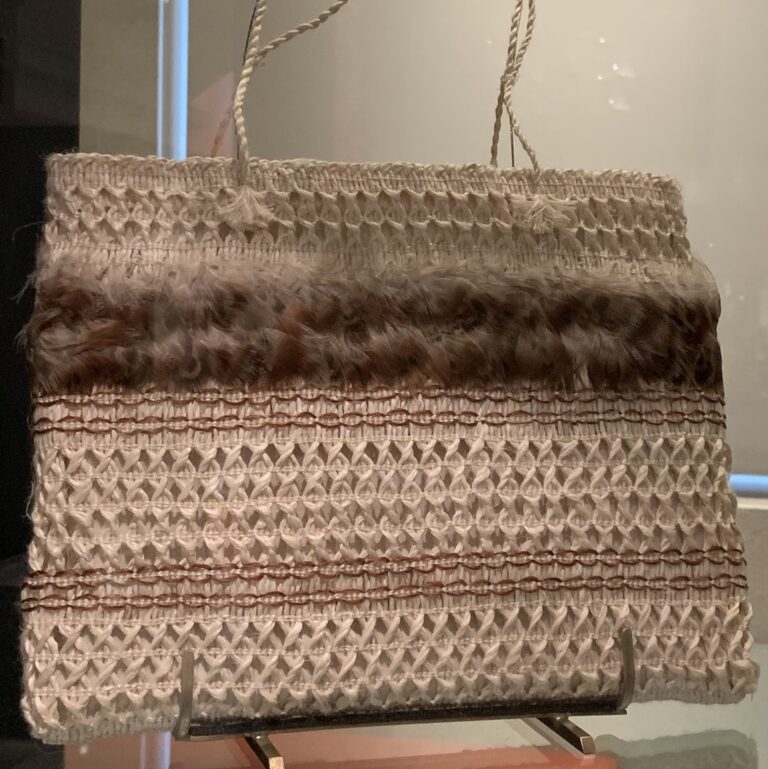

On that trip, eleven years ago, I spent hours upon hours in the Maori Court of the Auckland Museum and had barely gotten through that collection by the end of the day when I realized I had no time for the remarkable work in the other Pacific Island galleries. Fast forward to this recent trip, where I prioritized revisiting the museum before heading north to CollabNZ. Some aspects/pieces were familiar while others seemed new or perhaps it was that I was looking with different eyes while studying the innovative applications and unique aesthetics of harakeke on display. Above left is a piupiu with fine parallel lines cut across the leaf so that this narrow exposure of muka fiber could accept the dark dye and on the right, a meticulous kete of softened muka fibers illustrating the mawhitiwhiti, cross-over technique, and embellished with feathers. Indeed, there had been a redressing or changing out of the textile cases since 2012 and I invite you to visit this link for the museum where the need to do this is explained beautifully and where you can also see an image of the main case where several of these pieces I photographed are currently housed. Needless to say, I barely got through the Maori Court again and luckily had another day to go back for the Pacific Lifeways and Masterpieces Galleries this time. A must visit if you ever find yourself in Auckland!

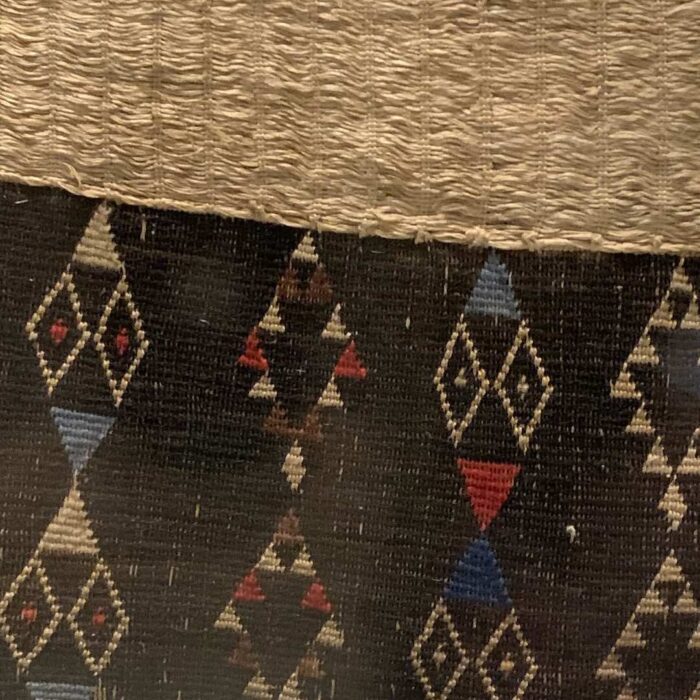

On display in the Auckland Museum, as well as in the tremendous book, Whatu Kakahu/Maori Cloaks published by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, which I had brought home with me in 2012, I observed only a small amount of wool fiber in Maori textiles, specifically cloaks. As seen left in the Auckland Museum, pixelated points of colored wool are revealed in the taniko, the dense border designs of the otherwise flexible muka base (kaitaka), by using multiple colored wefts and varying the twist of the weft-twining. Wool was also used in paheke, the looping of yarn into the weft of the muka cloak base to create contrasting linear elements and also in pom poms/tassels, though many tassels were kuri hair, the now extinct Polynesian dog.

The only sighting I made of anything resembling felt in the Auckland Museum were tassels on the Taiaha, a long staffed weapon with a carved spear resembling a head and jabbing tongue. These awe or dog hair tassels seemed far more likely to have formed into the matted tuffs on the dog though, rather than resulting from the intentional felting by a person.

I began to ponder Maori perspectives of the wool industry that came to Aotearoa with colonization and wools use, or lack there of, in Maori traditional as well as contemporary textile arts. I, an artist working primarily with wool, am interested in ideas of space, boundaries and intertwinement and find apt sociological metaphors in the felting of individual filaments or groups of filaments into a singular mass of felt. I thought perhaps the collabing of native harakeke leaves and wool felt could speak symbolically to colonization and reconciliation or, at the very least, the proximity and merging of different cultures.

Elke was game for a collab and we decided on a circumference for the midline of the vessel form. She built the base from harakeke early in the week and I was to develop what would be the shoulders and neck of the vessel. I have never woven flat strips of bast fiber into 3D form and had a lot of preconceived ideas as to how the harakeke rim of Elke’s form could integrate into small slits I intended to make around the belly of my felt form. Elke, I will take the liberty to say based on our conversations, was similarly unknowing of how my felting of a very large layout with what looked to be surface designs would become a postured form with armature-like protrusions using extreme differential shrinkage and directional fulling.

So there I was, well into the evening of the last making day of Collab NZ 2023 when my felt for the top of the vessel had dried. Not knowing how to bring these two halves into one unified form as well as the metaphoric weight I had placed on the piece, I procrastinated, prioritizing other smaller projects with more confidence. Though overlapping the harakeke edge with the wool felt and the need for a third party (a needle and linen thread moderator) to bring together the two different materials/processes is less graceful, visually and metaphorically, then I had hoped for, Coming Together was “collab good.” We can keep trying over the distances that separate us, in fact, this is the best metaphor of all.