It began the first day of Collab NZ with being asked to make a small concave felt bowl for another artist. No larger than the cup of my hand, the felt was to be inserted into a cavity carved into a foam chest of a pre-existing doll to hold an anatomical heart. The easiest way to get the curved bowl and the size desired was to raise a sphere of felt from a 2D template and once fulled, or nearly so, to cut the sphere in half and seal the cut edge. With the table of harakeke weavers next door, I asked for a few strands of their processed muka fibers. I laid these on the template before wrapping the wool to see what kind of texture I could achieve with one fiber shrinking and the other resisting the inward pull and therefore, looping off the surface.

Actually, it began my first day in Auckland. Having arrived from Chicago at 6:30 AM, I made my way to the Auckland Museum within hours of arriving. The local I was staying with insisted I attend the highly regarded Maori Cultural Performance at the museum and I did. I had never seen traditional poi spinning in action (as compared to modern fire twirling) and the two wahine amazed me with the rhythm kept while also singing, sometimes with two long poi in each hand, moving in and out of the others, without whacking anyone or loosing their flow.

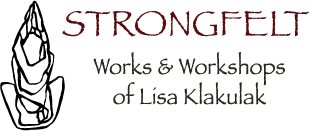

After the performance, I set eyes on this set of poi taniko made with all natural fibers in the Maori Court of the Museum. I was particularly drawn to the layering of textures. The walls of the spheres were constructed with twined muka from the harakeke plant (Phorium tenax). This fine surface was then overlayed with a diamond pattern created by wrapping strips of kiekie leaf (Freycinetia banksii) around the cross of thread. The seed heads from the raupo (Typha orientalis) were then used for stuffing the form. Here is a site online I found useful for learning more about New Zealand fibers that in many occasions were just listed by name in the museum, Manaaki Whenua/Landcare Research.

Back at Collab NZ now, meet Jo Tito on the left, a Maori artist whose work focuses on native fibers and dyes, seen here sharing a sweet embrace with Denise Wallace, a jeweler of native Alaskan Chugach Sugpiaq heritage. I invite you to look at both there websites! Jo was also set up in the fiber tent working with harakeke, but unlike the weavers I wrote about in Part 2 of my CollaboratioNZ blog posts, Coming Together, she was making paper with the fiber in the coolest transportable Hollander beater. Pictured on the right, is a collection of her papers, harakeke seed pods, their seeds and the glass muller used to make ink from the pods. A little more about the ink later in this blog posting…

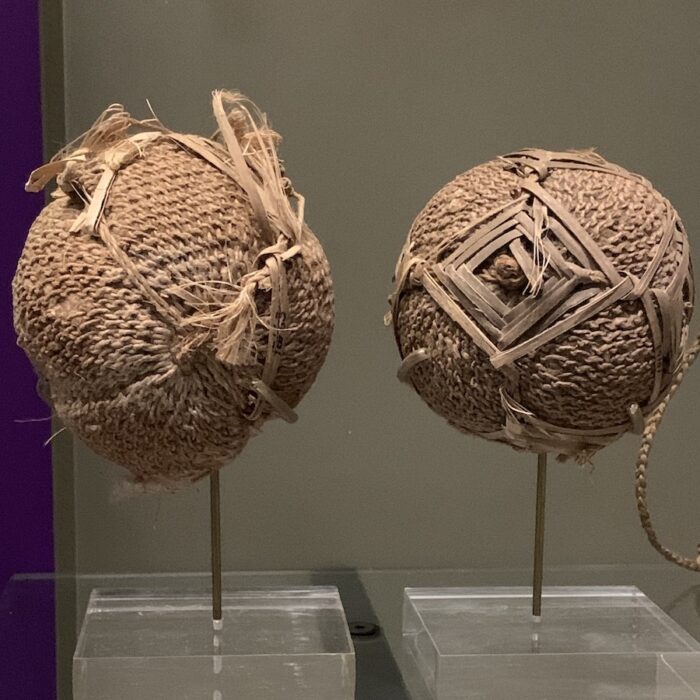

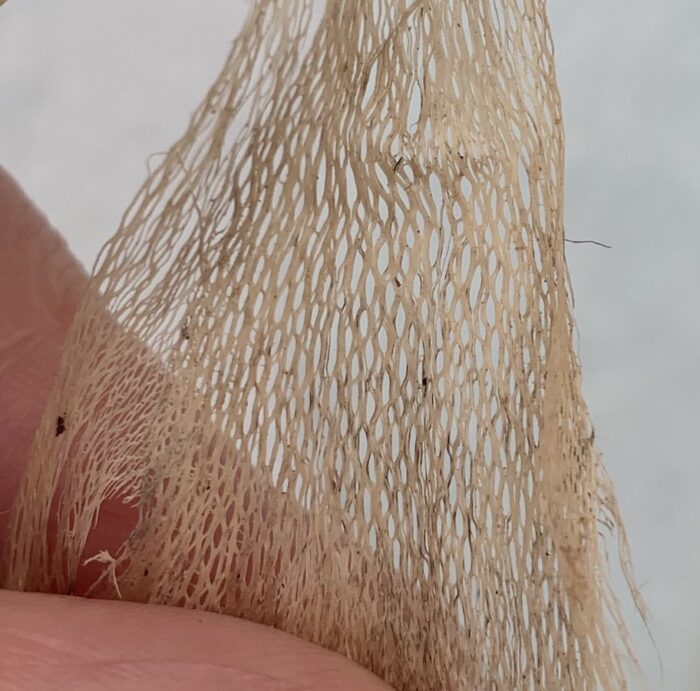

I had thought about those poi I had seen in the museum when I was felting the hollow sphere with the muka fibers looping off the surface. Wouldn’t a set of all natural felt poi be an interesting exploration for a collab? Jo generously shared her insights on the size I should make the poi and offered strips of the most amazing lace bark (Houhere) she had brought along to Collab seen in its splendid detail on the left below. I was curious how the wool fibers would move though the mesh of the bark and contort its ribbon like formation. I laid it as a center line on the template to assist me in felting the wall of the sphere consistently along with some natural muka fibers on one hemisphere and others, indigo dyed in a vat set up by Lindsay Embree, on the other half.

Of course, I would need ropes for the poi so they could be twirled! I had seen beautiful plaiting work done by Wendy Naepflin, one of the flax weavers, and she was game to collaborate. She knew the length for a short set of poi and suggested a four plait with muka filaments that had a natural reddish color and also those dyed in the indigo vat. How beautiful are these ropes for this set of short poi?

The last component for these all natural poi was to determine the fill material. With all the harakeke leaf processed to reveal, isolate and soften the inner muka fiber, there was a bucket full of dried para, that scraped outer flesh of the leaf. Perfect, however, I had left only a small hole for the knotted end of the rope to be inserted into the felted sphere, so packing the para inside with the end of a wooden skewer was quite the long process. Through out it, I kept handing the set over to Jo for her to ascertain whether they felt like the right weight. Jo also guided me in my first poi spinning lessons and I found the coordination really challenging and the experience rather hilarious! Although, my spinning didn’t have near the grace of a birds flight, the golden looping muka fibers on the surface of the felt nor the skills demonstrated by the Maori women I witnessed spinning, Jo and I settled on the title, “Flight of the Muka.”

I had mentioned that Jo Tito had made some ink from the harakeke seed pods. She and Hamish Oakley Browne, a printmaker who is the director of the Te Kowhai Print Trust at the Quarry Arts Center in Whangerai, had collabed on some relief prints using the harakeke ink and paper. I was interested to see how that Korari ink would print on a fine merino wool felt and so was Hamish. He had suggested using a lino cut he had made illustrating the story of Te Wheke a Muturangi. It goes something like this, based on hearing a few renditions and reading a few more online..

A man named Muturangi had been banished by villagers to a remote island in Hawaiki, the ancestral home of the Maori. He became familiar with an octopus who then stole the bait off of the fishmermans’ lines in revenge. Kupe the explorer went to battle with the Octopus across the Pacific and this battle to slay the Octopus was responsible for shaping the Cook Strait that separates the North and South Island of Aotearoa/New Zealand. I envisioned the battle with all 8 long arms in the water and thought about the wet felting process and the intertwining filaments.

I took the measure of the lino and sized it up for 80% shrinkage and laid out a far larger area with a specific weight of wool. The finished felt was tight and suede-like especially after a nice clean shave so that the fuzz wouldn’t effect the clarity of the print. Hamish made a beauty of a print! Camilla Harmstron and I brainstormed a manner of presentation so that the luxurious drape of the high shrinkage felt would be evident and play off the visual movement of the octopus tentacles. Bex Asquith devised a wall cleat that allowed for easy hanging. Lastly, I decided to stitch several strands of muka through the felt to honor the rich tradition of fish hooks using twined muka lashing and to add a bit of warmth in color to balance the wood clamp of the hanging device.

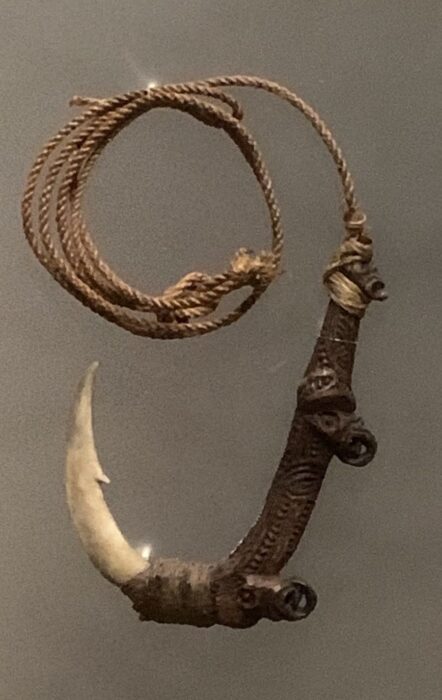

The universal use of fiber to wrap, hold and bind was certainly evident in the Maori Court of the Auckland Museum: cloaks, wall panels and mats, bags, fishing nets/traps and the lashing of tools. I took particular notice of the collection of fishing hooks with their finely twined muka lashings that bound the hook to line, but also the barb to the shank. You can observe that the largest wooden hook above appears to be two limbs that have grown in that configuration and that the bend was carved from the shared wood base/trunk. This natural growth provided more strength and therefore less lashing, just a bit of muka twine across to lessen the tension on the wood when bringing in a big one! There were so many different designs and materials matching the variety of fish and means for catching them. Some were ornately carved too, like this beauty pictured to the right. As a maker of fiber/felt-based jewelry, I am inspired by their sizes, curves, and tapers, as well as the variation of smooth and textured areas. With life dependent on the waters, it’s no wonder that fish hooks, hei matau, became adornment representing prosperity and safe travels over the waters for the Maori.

This Part 3 of my CollaboratioNZ 2023 blog posts, Muka Fiber in the Air and Sea, concludes my documentation of pieces made in collaboration, connections started with other artists/makers and new learnings about Maori culture from this particular event. Thank you again to CollaboratioNZ Trust and the North Carolina Arts Council for your support providing this opportunity. It was an experience not to be forgotten.